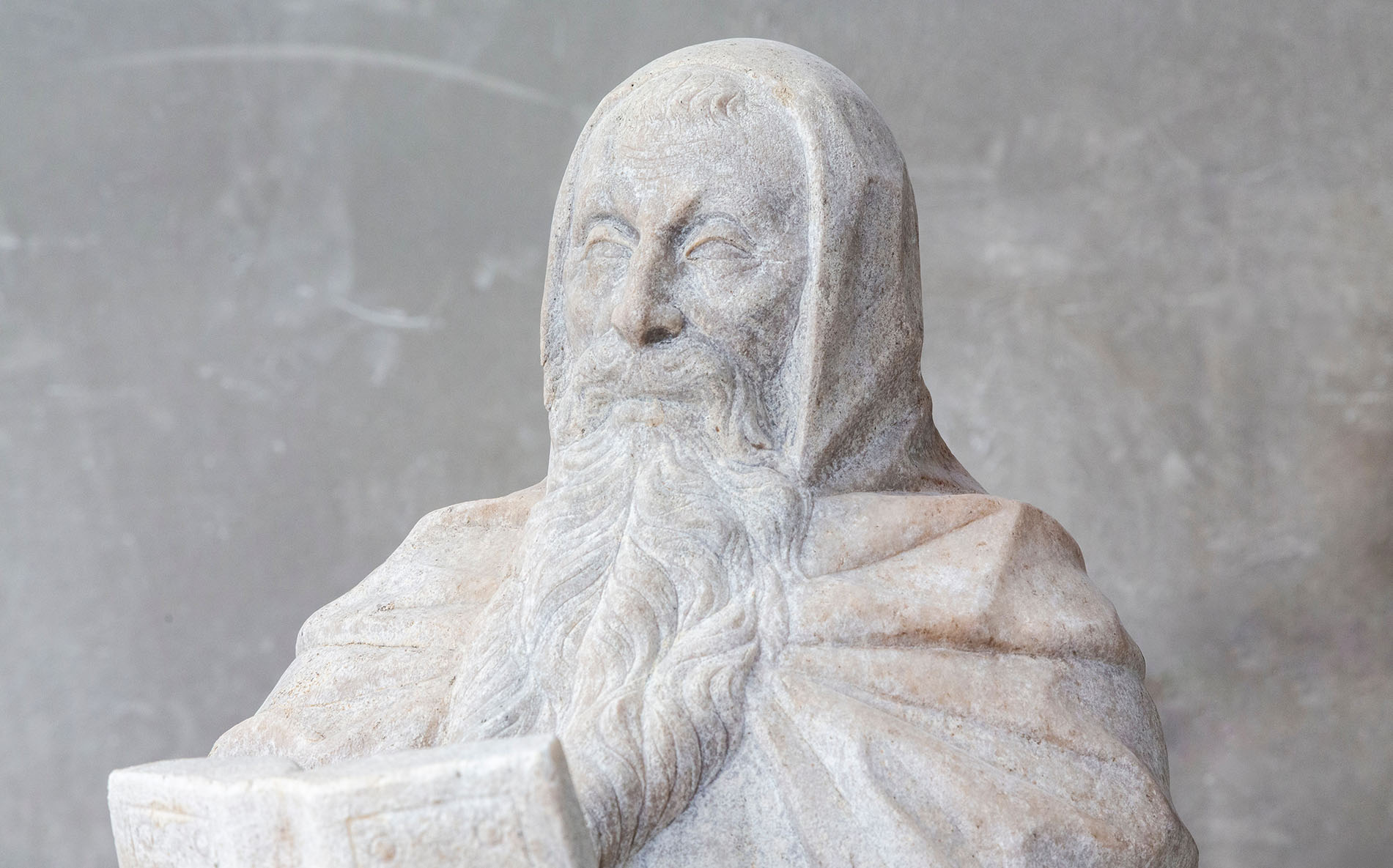

The statue on the top of the G65 spire is a Roman general, placed on the south side looking towards Piazza Fontana, this time it does not seem to be a holy martyr, but rather a professional soldier, maybe later converted. This figure perhaps wants to remember that Mediolanum which at the time of Augustus was already an important subalpine city, and which became the capital thanks to the work of Maximian. A Roman emperor was also born in Mediolanum, a certain Didius Julianus, who went down in history as the man who bought the Roman Empire at auction after the death of Antonin Pius, even if his glory was ephemeral, since Septimius Severus succeeded him in a short time. But Milan was destined to remain in the crucial area of the Western Empire: here Constantine proclaimed the edict that would make all religions equal. The statue looks towards Via Corsia dei Servi, once home to the Erculean Baths, where the he must have gone many times to rest after the hard winter in Germany or Britain.

Tales of the statue in Dome’s building site:

The original statue of the Soldier of Mediolanum is the work of the sculptor Gio Battista Raggi, presumably dating back to the early 19th century. The annals also testify to the fact that the sculptor was Raggi, in which a payment to the artist appears. Today the G65 spire is occupied by a reproduction of it.

Tiburio

Tiburio